Siemens Healthineers MedMuseum

Discover (hi)stories

- The Siemens-Reiniger-Werke under National Socialism

The Siemens-Reiniger-Werke under National Socialism

The largest specialist electromedical company in the world

The commercial register entries in Fürth and Berlin in January and February 1933 marked the first time that the founding companies of the medical technology arm of Siemens had been combined into a single enterprise: Siemens-Reiniger-Werke (SRW). The new company was officially headquartered in Berlin, in a building known as the Haus des Arztes (“House of the Doctor”). Located in the immediate vicinity of the famous Charité hospital, the building was home to the company’s administrative and sales departments, which were led by Theodor Sehmer, a member of the company’s board. The headquarters of SRW in Berlin incorporated exhibition spaces and grand rooms for customer visits, whereas the company’s manufacturing and technical development were brought together in Erlangen under the leadership of the board member Max Anderlohr. This meant that Siemens-Reiniger-Werke was essentially under dual leadership – and the link with Siemens & Halske (S&H) was maintained by Heinrich von Buol, who was both a member of the board of S&H and chairman of the supervisory board of SRW. He was also frequently required to mediate in disputes between the two SRW board members.

“The Haus des Arztes (‘House of the Doctor’) in Karlstrasse 31, Berlin, head office of Siemens-Reiniger-Werke AG and home to the SRW branch office in Berlin,” 1933–1935

X-ray tubes were produced at the factory in Rudolstadt, Thuringia. As the site expanded, it incorporated the company’s X-ray research laboratory from the financial year 1935/36 onward. The Erlangen location also underwent expansion in the 1930s to become the main production site, where the company produced all of its electromedical products except for electrocardiographs, X-ray dosimeters, and hearing aids. Several new buildings planned by the Siemens architect Hans Hertlein expanded the production area to almost 15,000 square meters, arranged around two inner courtyards. A factory medical department was also established in 1935. At the same time, the number of employees grew from around 900 in the financial year 1932/33 to over 2,100 in 1938/39 – which in those days accounted for 10 percent of Erlangen’s workforce.

In the 1930s, SRW experienced an upturn due to increasing sales of its products for two key reasons: Firstly, the company began to receive a growing number of government orders as part of domestic preparations for World War II. Secondly, it launched a series of innovations that were highly sought-after both in Germany and abroad. Foreign sales remained consistently high during the 1930s and stood at over 50 percent in 1936. The unified marketing style that Hans Domizlaff introduced across Siemens and all of its subsidiaries in 1935 helped the companies to present a consistent image in their advertising for the international market. The logo that was designed for SRW featured a dominant S entwined with the Reiniger R. In addition, Siemens-Reiniger-Werke had a large network of foreign branches at its disposal: From Shanghai to Buenos Aires and from Montreal to Calcutta, the company maintained offices across the globe – many of which had generously sized exhibition spaces in which international customers could see the quality of the medical technology produced in Erlangen and Rudolstadt for themselves. In those days, the company was also present at major international conferences for medical technology. It is therefore no surprise that Siemens-Reiniger-Werke was considered the largest specialist electromedical company in the world prior to World War II.

Products of that time

In Germany, many of these medical products ended up in the hands of physicians who abused the technology to serve the barbaric ideology of National Socialism. Although the X-ray Bomb was developed for treating cancer, some physicians also used it to perform forced sterilizations.

X-ray Spheres

The Siemens X-Ray sphere is one of the most successful products of the Siemens-Reiniger-Werke. This X-Ray device for diagnostics is a single-tank unit. The X-ray generator and tube were housed in a joint casing that was safe to touch and also radiation-proof. Launched in 1934, this product was sold in its thousands over the course of several decades and achieved almost iconic status as a result of its extravagant design.

X-ray Bomb for treating cancer using deep X-ray therapy

The single-tank principle also began to make inroads in the field of radiotherapy, where Siemens launched a product known as the “X-ray Bomb,” which was designed to treat cancer using deep X-ray therapy. Mounted on a mobile stand, the approximately 300-kilogram radiation head allowed versatile adjustment and easy operation despite its immense weight. Almost 300 X-ray Bombs were built in the period from 1938 to 1943

Pantix rotating anode tube

The “Pantix” rotating anode tube were developed at the factory in Rudolstadt. This device was ready for launch in 1933 and went on to become a worldwide best-seller. X-ray tubes are still based on the principle of the Pantix tube to this day

Ultratherm

Advertising photo depicting treatment with the Siemens Ultratherm, 1936: The device could heat body tissue up using ultrashort waves. During the war, a portable version was developed and used to treat frostbite in soldiers.

Konvulsator for electroconvulsive therapy

One typical innovation of this era was electroconvulsive therapy, whose use is often seen as controversial. For this type of therapy, Siemens-Reiniger-Werke worked with the Psychiatric Clinic in Erlangen and the Psychiatric Hospital in Eglfing-Haar, near Munich, to develop and test their own device, which was known as the “Konvulsator.”

The company under National Socialism

The year 1933 marked not only the founding of Siemens-Reiniger-Werke but also the installation of the National Socialist dictatorship. The country’s new rulers quickly took complete control of life in Germany and infused it with their racist and anti-liberal ideology. These developments also had an immediate and direct impact on SRW. In spring 1933, the Works Council in Erlangen was dismissed in response to pressure from the local Nazi leadership and replaced with a Council of Trust that was partly made up of long-standing members of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP). The Work Order Act introduced the Führerprinzip (“leader principle”) at all companies, reducing employees to the status of mere “followers” of the factory leader and putting an end to any vestiges of democratic codetermination. On May 1, 1933, Siemens-Reiniger-Werke also celebrated the first “National Labor Day,” which saw the staff of SRW gather in the factory yard for a speech by board member Max Anderlohr, and then join other groups to march through Erlangen under the leadership of the Sturmabteilung (SA). The following day, the Nazi regime disbanded the independent trade unions, soon to replace them with a unified workers’ association known as the “German Labor Front” (DAF). Although membership of the DAF was voluntary at first, the company management put pressure on staff to sign up. The membership fee was deducted directly from the workers’ wages.

March through Erlangen on the occasion of "National Labor Day" on May 1, 1933

Subsidiary organizations of the DAF, such as Kraft durch Freude (“Strength Through Joy”), organized vacations and leisure activities – although this provided another way for the DAF to exert social control and encouraged the spread of National Socialist ideas. The company introduced the Nazi salute at its Erlangen and Rudolstadt factories in August 1933 as a visible expression of the newly established “factory community.” As a result of the enactment of the Nuremberg Laws, board members and authorized signatories had to provide proof of Aryan ancestry in order to continue receiving government orders. The extent to which human-resource policy was shaped by racial ideology is illustrated by an incident that took place in January 1939, when the SRW branch in Rio de Janeiro took out a newspaper advertisement seeking a Brazilian citizen of “Aryan extraction.” This led to an outcry in the South American country, with demonstrators laying siege to the SRW offices and the managers temporarily being placed under arrest. The fear of a negative impact on foreign business meant this was a disaster for the company’s head of sales, Theodor Sehmer.

Notices from the German Labor Front (DAF) at the Erlangen factory in July 1939: The appeal to engage in sporting “good-willed competition” and the notice that reads “Cook well! Keep good house!” exemplify the measures adopted under National Socialist policies. The idea was to keep the population healthy and efficient for the impending war. The swastika in the DAF’s gearwheel symbol was blacked out in the postwar period.

Wartime economy and forced labor

The outbreak of World War II in September 1939 was a major turning point for Siemens-Reiniger-Werke, and the company became even more deeply integrated into the state-managed economy of Nazi Germany. Just as in World War I, the company saw part of its foreign sales collapse. However, it managed to continue supplying medical technology to neutral countries, and especially to the important South American market, via companies in Italy, Spain, and Sweden until 1942. Nevertheless, it became much more difficult for SRW to do business internationally. Despite this, SRW enjoyed growth not only in turnover but also in the size of its workforce. There were two reasons for this: Firstly, the volume of public contracts for the German armed forces continued to grow rapidly – with particularly high demand for field X-ray units, along with other electromedical products such as metal detectors or “Ultratherms” to tackle frostbite. By the financial year 1939/40, production for the armed forces made up 14 percent of the company’s output.

Manufacturing of the heavy field X-ray units for the armed forces, 1940

From 1941 onward, with incoming orders for electromedical products already exceeding the production capacities of SRW, its management began awarding contracts to companies in the occupied territories – particularly in France. The priority here was to supply the German armed forces, followed by hospitals, and then private customers. In 1943, SRW’s production of electromedical equipment was designated as being vital for the war effort, which had important implications for the allocation of resources and staff. Secondly, from the financial year 1936/37 onward, the company complemented its production of electromedical equipment with a specialized manufacturing section for military hardware that had nothing to do with medical technology. Before the war, SRW was primarily engaged in the construction of radio equipment and directional gyros. Later, it also began producing a homing receiver known as the Ludwig device. These products were manufactured under license from the Siemens holding company Luftfahrtgerätewerk Hakenfelde GmbH in Berlin. No armaments were produced in Rudolstadt; the factory was struggling to clear the backlog of orders for X-ray tubes from the prewar years, a job made all the harder by the steady stream of new orders coming in. At the same time, specialized nonmedical manufacturing in Erlangen was playing an increasingly significant role for the company both economically and in terms of human resources – and accounted for 50 percent of turnover in the financial year 1944/45. The importance of the factory was highlighted when, on January 1, 1941, SRW board member Max Anderlohr was appointed as a Wehrwirtschaftsführer – a title awarded to executives of companies that were vital to the defense economy. In 1943/44, as the war raged on, the factory reached its highest number of employees to date, at over 3,000 people.

An appeal to staff of Siemens-Reiniger-Werke to submit suggestions for improvements in order to save valuable materials during the war, August 1942

The composition of this workforce, however, was different to that before the war. Large numbers of employees – 600 of them by the financial year 1941/42 – had been conscripted into the armed forces, thereby reducing the proportion of men. Over that period, vacancies had primarily been filled with German women. As of February 1941, however, the positions were increasingly filled with prisoners of war or conscripted foreigners – initially from occupied western areas such as France. In March 1942, following the attack on the Soviet Union, the company also saw the arrival of the first forced laborers from Russia and Ukraine. The proportion of workers from abroad rose steadily, reaching a maximum of 900 people from 15 countries in July 1943, most of whom were put to work in the specialized manufacturing section. The forced laborers were subject to a hierarchy based on the racist principles of National Socialism. Those with the lowest status were known as Ostarbeiter (“eastern workers”), and around 80 percent of them were women. Unlike forced laborers from occupied western areas, they were not housed in rented guest rooms but rather in specially constructed camps with wooden barracks, where the inhabitants were not only exposed to poor sanitary conditions but also insufficiently protected from the cold in winter. SRW paid Ostarbeiter less than their western colleagues, and gave them the smallest food rations. The management endeavored to prevent contact between the German workforce and the Ostarbeiter, who could not move around freely and had to remain in their guarded camps. To provide the Ostarbeiter with some distraction from their strenuous everyday lives, SRW organized occasional events and parties that served as a cheap and easy way of maintaining their motivation to work. After all, the company was reliant on its workforce, and the female Ostarbeiter in particular were seen as being especially conscientious and disciplined workers.

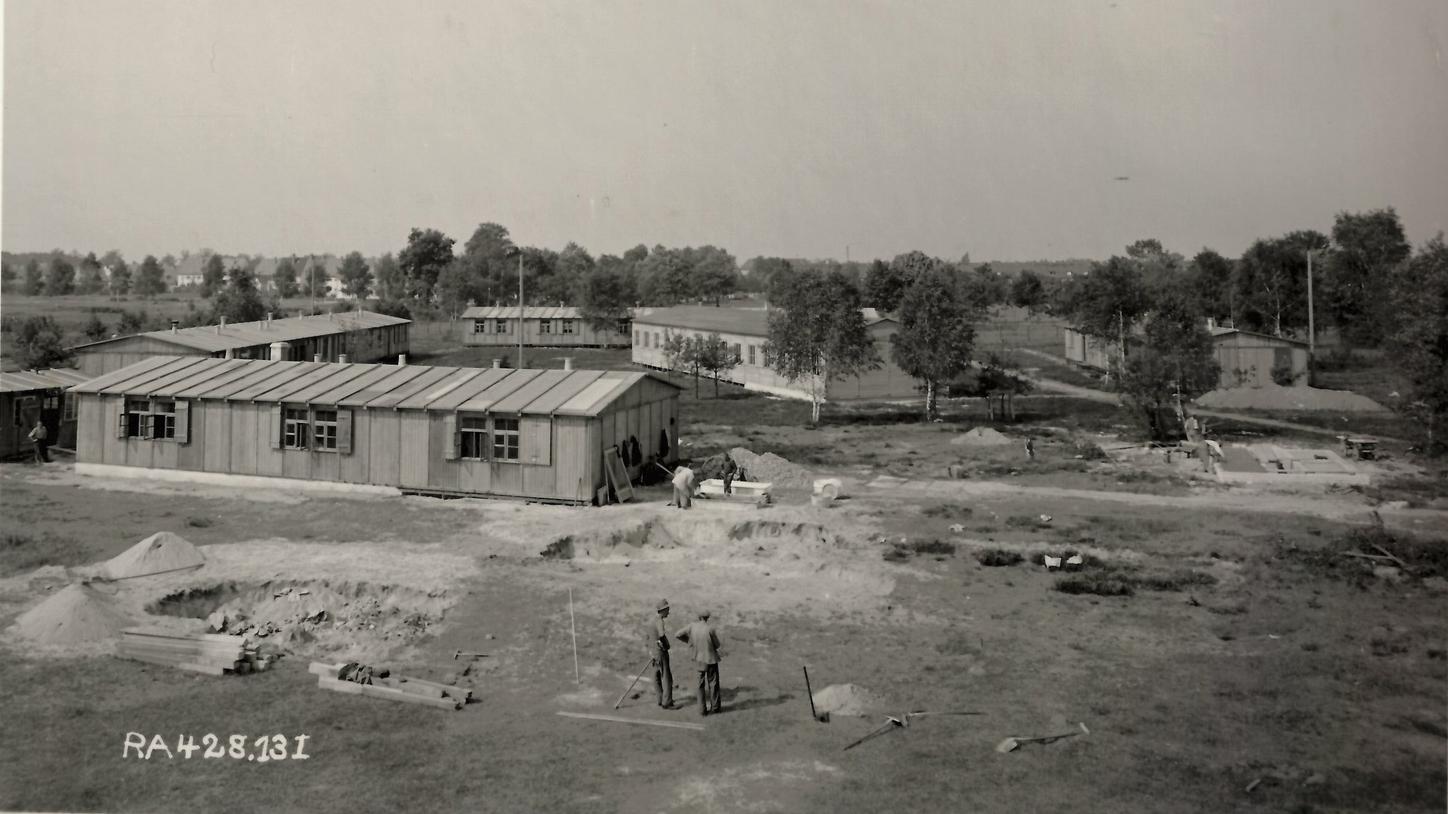

Construction of the Röthelheim camp, which had up to 500 beds for Ostarbeiter, 1942

To raise morale and productivity, parties such as this Christmas celebration were staged for the forced laborers. Pictures like this belie the poor conditions under which the Ostarbeiter in particular suffered.

The end of the war

From 1943 onward, with Berlin under increasing bombardment, plans were put in place to relocate those manufacturing activities that were vital to the war effort. Against this backdrop, the SRW headquarters were gradually relocated over a period lasting from 1943 to just before the end of the war. The sales offices were moved to Erlangen along with the financial administration, technical sales, and advertising departments. Following the Allied occupation of Germany, both Rudolstadt and the SRW headquarters in Berlin found themselves within the Soviet Occupation Zone. As the war came to an end, a great many offices in Germany lay in ruins, but the factory in Erlangen was handed over to American troops intact on April 16, 1945. On May 8, 1945, the day of Germany’s surrender, the first sales meeting was held at the newly liberated factory.

The undestroyed SRW factory in Erlangen, 1948

Spezialist für Historische Kommunikation und Historiker im Siemens Healthineers Historical Institute